Jasmine Miller

GUEST BLOGGER

“I was in my therapy group the other day … ”

That’s the kind of honest conversation starter even a stranger will get from Don Kerr, a man who’s not afraid to tell you about his struggles with depression or arguments with his wife.

“One of the guys asked how I was feeling and I said, ‘I’m angry. I’m full of rage.’”

It sounds like an equally honest answer and certainly a reasonable one, considering what Don and his wife, Kate, have just come through.

Until the Friday afternoon in October 2011 - when Kate got the call telling her she had breast cancer - the couple had a good life, but they were, as Kate says, “on auto-pilot.”

Sons, Gabriel, now 5, and Samuel, 3, were the main focus. Kate, 39, worked as a senior executive at a creative agency; Don, 53, ran his own business from home, with enough time and flexibility to pick the kids up from Montessori.

“But cancer changes everything forever,” Kate says - and she’s not talking just about the logistics of life.

The therapy group meets for a couple hours once a week, not far from the Kerrs' Oakville, Ontario home. It's helped Don process the “14 months of hell” that followed Kate’s diagnosis—months that included Kate’s mastectomy and lymph node surgery, a winter of chemotherapy and a summer of radiation treatments. But as Don mulled over what he said recently to the group, he decided his answer was a lie.

“I went home and thought about it and realized actually, I’m not angry. I’m scared s--tless,” he said.

The distinction between rage and fear can be tough and, as Don will tell you, it is especially so for men.

“The way we were brought up is you can’t be afraid, because that’s not helpful. You have to be brave and courageous and stand up and fight the dragons,” he said.

And when men join the ranks of caregiver, being unable to name their feelings, let alone talk about them, is a liability for caregiver and patient both.

“I struggled with the prospect of losing the most important person in my life, but also with the helplessness that you feel along the way,” Don said. “It’s a peculiar, male notion, that idea that ‘I’ll fix this.’ But with cancer, that’s not going to happen.”

That lack of control, Don explains, breeds fear that masquerades as anger.

“The anger part is very real on two fronts,” Don will tell you. “As the caregiver, you become the receptacle for all the anger your wife wants to express and she has nowhere else to put it.”

When asked for an example, Kate looks at her husband with softness and a subtle tilt of the head: “Half way through chemo, I would say to Don, on a daily basis, ‘I would rather be dead.’ And I meant it.”

(Anti-nausea medication didn’t work for Kate, as it doesn’t for about 10 per cent of people.) Back then, Don heard an accusation.

“It was said like it was my fault, and I believed that,” he says.

“The other part of the anger is you’ve got nothing to do, nowhere to go,” Don says.

That’s the part he wants to “fix”.

At the hospital where Kate was treated, “they had tons of pamphlets,” Don remembers. “What I found is that there is a pant-load of stuff for the person with cancer, but very little for the male caregiver.”

Kate attended meetings with a psychiatrist (“As a patient, you’re very worried about being a burden to everyone around you,” she says), and when she asked if there was a similar service for caregivers, she learned that there was, at one point, but the program had been cut. Don would have to find, or create, his own support.

“I went online in a blind quest,” he remembers. That's when he found the former facingcancer.ca, now Facing Cancer Together.

"It was a space that offered support and insights, but still, “there wasn’t much here for me specifically.” So he joined the community of bloggers by starting his own.

Don acknowledges that Kate did the heavy lifting of confronting her cancer—he describes his role as “riding shotgun,” reflecting the fact that as caregiver he is not in the driver’s seat on this journey.

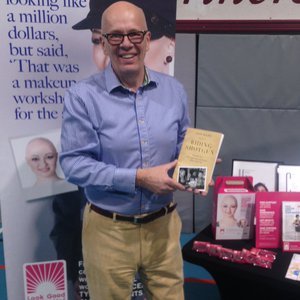

“Riding Shotgun” is also the name of Don’s blog.

“I didn’t know this was going to be a therapeutic exercise,” he says, “I just knew it made me feel better. It allowed me to express my concerns, fears and anger in a way that was safe.”

Safe from what?

“Guys don’t do this,” he says. “I was worried about putting myself out there to potential ridicule and judgment. But when there’s a question of losing your partner, the judging becomes less important.”

Within hours of receiving Kate’s diagnosis, Don reached out to his network, focusing on people in the medical industry. Kate remembers that he said, “We don’t know where to go, we don’t know what to do. This is what we’ve been told. Can you help?” That digging led to the oncologist who explained that Kate’s original diagnosis was wrong and provided the treatment plan Kate would ultimately follow.

Those were Don’s baby steps into an honest caregiving role — being vulnerable and admitting to confusion, while moving forward and filling in where Kate couldn’t.

“Don did the research, reaching out to people and bringing back new learnings, new insights every day and thank God he did,” says Kate. “He channeled that back to me. He was my link with the outside world and men don’t traditionally play that role even in a relationship with no cancer. He was my lifeline because I would never have done that. Not only has he seen it all and heard it all, and he’s still here, but he was my link to the outside.”

Don also took over the family’s communications strategy. There were people who needed to be kept in the know about Kate’s progress and Kate herself wasn’t able to do it. Don started a regular email to a group of about 100 people he calls “Katie’s Karma Corps,” the friends, family and coworkers who join on fundraising walks, bring homemade soup, check in and check up on the Kerrs.

And where he can, Don has joined Kate in the new lifestyle she embraced as part of her healing. This includes her intensive three-year program in Interpersonal Neurobiology and Meditation, started to help cope with chemotherapy and now expanded to help her thrive after it. Don has completed a 12-week meditation course.

“I call myself Grasshopper compared to my Zen-master wife,” he says.

Treatment is finished now, Kate’s brown hair sleek, short and full; she is naturally slight, and enviably fit from the daily 5km runs and 30-minute yoga sessions that she started in preparation for chemotherapy and will forever be part of her routine.

“People have to know that when you go through this,” Don says, looking into his hands, twisting a coffee cup sleeve into a piece of origami for Kate, “some absolutely horrid, awful, despicable things will be said.”

And while it’s clear that all is forgiven, the journey isn’t over (Kate’s health will always be a priority, sometimes a source of fear).

When people ask him how he stays sane, Don answers honestly: “I don’t,” he says.

Sometimes, as the caregiver, “you are in the darkest, deepest canyons and chasms and you think ... ‘I need this to be over,’” he says.

Instead, he takes his own advice and continues to reach out for support, and to share as honestly as he can.

“If my blog does nothing else but get two guys, maybe three guys, to admit that they’re scared and they don’t know what to do about it, I will have done my job,” he says.

Buy Don's book Riding Shotgun on Amazon, or visit his website.